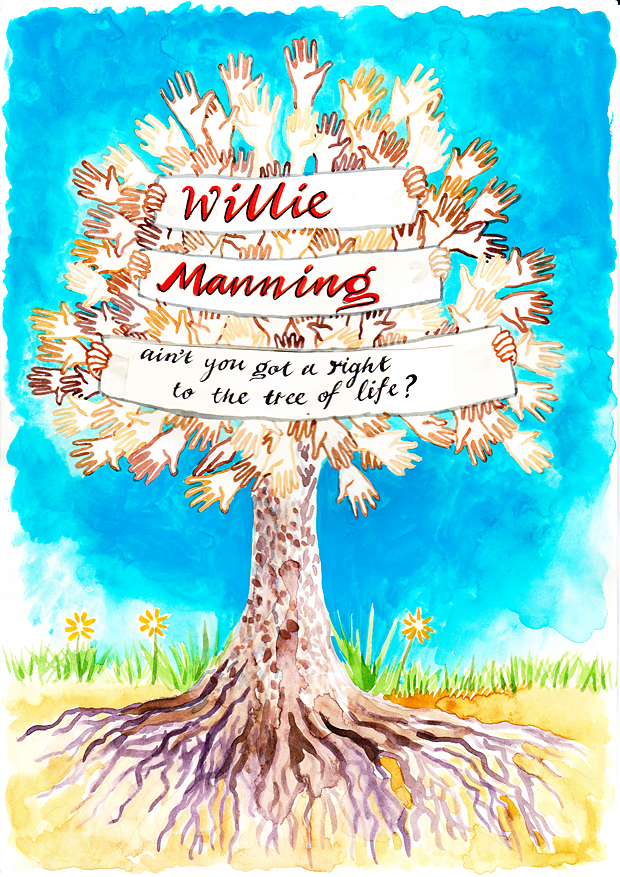

Image: Manning (Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, Tupelo, November 1, 2024)

Willie Jerome Manning, on death row in Mississippi, was convicted at two separate trials of two unrelated double murders. He was exonerated of one of his convictions (Jimmerson-Jordan murders) on April 20, 2015, because the key witness recanted, saying his testimony had been coerced by the prosecutor and prepared by police; significantly, the prosecution withheld evidence that showed this witness must have been lying. If this evidence (police canvass notes) had not existed, or had not been withheld, Willie could well have faced execution on the basis of false, coerced, recanted testimony. (See more about this case below, at

1993 JIMMERSON-JORDAN CASE [BROOKVILLE GARDEN CASE]: EXONERATED)

Willie is still fighting his other capital conviction (Steckler-Miller murders), for which he came within hours of execution on May 7, 2013. He has always maintained his innocence in this case.

Forrest Allgood was the prosecutor in both Willie’s cases—and in six other wrongful conviction capital cases in the same judicial district. Sheriff Dolph Bryan was also involved in both of Willie’s cases (see more here).

The rules of the US death penalty system and the “materiality” rule make it extremely difficult for an innocent death row inmate to be granted a new trial. Black Americans are “about 50% more likely to be innocent of the murder than other convicted murderers”, largely because of the greater incidence of police misconduct against black suspects.

1992 STECKLER-MILLER CASE

Events Leading to Willie’s Conviction

Students Tiffany Miller and Jon Steckler were found fatally shot on a country road near Starkville, Mississippi, at approximately 2:15 a.m. on December 11, 1992.

A white car, later identified as Tiffany’s, was noticed by a witness just before 1 am that night parked outside her apartment block in Starkville, not far from the trailer where Tiffany lived. Jon’s blood was later discovered on the car’s underside, indicating that he had been run over by a driver in the car. (See here – pp 7-8 and p. 36)

This sighting of Tiffany’s car calls into question the state’s theory of the timing of the murders: the state said that Tiffany and Jon left Jon’s Sigma Chi fraternity house between approximately 12:50 and 1:00 a.m. The state’s theory assumes that Tiffany’s car was parked outside the frat house; but at that very time it was seen outside the apartment block.

New evidence shows that another witness told the police that she heard gun shots and a man yelling that night at some time after midnight, from the direction of Tiffany’s trailer – she thought the voice was that of a white man. Strangely, the police failed to pursue this information. Had they done so, they would have heard corroborative evidence from at least one other witness.

The police investigation focused instead on reported theft from a car parked outside the Sigma Chi house that night. According to the car’s owner, the theft must have occurred by about 1.30 a.m., while the car was unlocked and undamaged. It is not clear why he added that by the morning the car was damaged.

The sheriff theorized that the reported car theft had been disturbed by Tiffany and Jon, and that the thief then took them away and murdered them. Fingerprints lifted from this car were not assessed until 2015, despite their significance in the sheriff’s hypothesis.

An experienced investigator later expressed surprise that the sheriff pursued this theory of a disturbed theft: the evidence – Jon run over, and Tiffany sexually assaulted – suggested a much more personal motive for the killings.

In pursuit of his theory, the sheriff doggedly interrogated various African American males suspected of car burglary. Remarkably, Willie Manning fell under suspicion when a huggie from the car reported as burglarized was found at a great distance – 5 miles – from Willie’s home. Nothing on the huggie linked it to Willie. (See here, p.9)

Willie had been at the 2500 Club on the other side of Starkville on the night of the murders; witnesses who were there at the time have confirmed this.

However, the sheriff used coercion and favors to persuade other, unreliable witnesses to testify against Willie (similar coercion and favors were later also used to convict Willie in the Jimmerson-Jordan murders’ case).

Under this pressure, Earl Jordan said that Willie had confessed to him that he (Willie) and another African American man had forced the two students into Tiffany’s two-seater car). His account was logistically impossible – four people could not have squashed into a two-seater car. It was also impossible because the man named as Willie’s accomplice was securely locked away in jail in Alabama at the time of the murders. Tellingly, the police did not pursue this alleged accomplice. See Motion for Leave to File for Successive Petition, September 29, 2023, Pp 10 -11 {Pp 14-15 of PDF).

The state quickly changed the trial narrative to its own – only slightly less preposterous – version of what happened. According to the prosecutor, Willie acted alone in transporting the two students with him in the two-seater car (while presumably – according to this theory – having also crammed in stolen items from the other car). It is unclear how a perpetrator could have controlled two victims in a two-seater car. (John Wise, the owner of the burglarized car, testified that “the only way to have three people in the MR2 was to have one on the other’s lap in the passenger seat”. See Petition for Post-Conviction Relief P.13, ¶ 36. {P. 21 of PDF}.)

Earl Jordan retracted his ludicrous testimony in 2023, explaining that the sheriff had pressurized him to inculpate Willie. See Motion for Leave to File for Successive Petition, September 29, 2023, Pp 10 -11 {Pp 14-15 of PDF). His testimony would have significantly influenced the jury’s verdict (the dissenting justices noted in September, 2024 that “Manning’s confession to Jordan removed this case from the circumstantial realm.”)

The jury was not informed that a different important witness was incentivized with a large amount of money, gifts and concessions to testify against Willie; the jurors were therefore unable to evaluate how freely her testimony was given.

The judge at Willie’s trial allowed an FBI expert to describe hair samples recovered from the two-seater car as belonging to an African American; this testimony was discredited in 2013 by the Department of Justice. Strangely, the trial judge later dismissed the hair evidence as being of no probative value. But the hair testimony must have influenced the jury.

Trial testimony by an FBI firearms expert was discredited in 2013, and even further discredited in 2023. But this testimony must have influenced the jury’s verdict. (See here – pp 50-79)

No witness claimed to have seen Willie in the parking lot; nobody testified that Willie was ever seen in Miller’s car. See Brief of Appellant, April 19, 2021. P.6 {P. 10 of PDF}.)

No physical evidence linked Willie to the murders. No physical evidence linked the reported car theft to the murders.

Recent Events

In September, 2023, Willie filed evidence that several state witnesses, including key witness, Earl Jordan, were incentivized into falsely testifying against him, and that new developments in science further invalidated firearms testimony given at his trial. (See WLBT article.)

The new evidence also reveals the failure of the state to follow up a witness statement describing a white male yelling, followed by gunshots, coming from the direction of Tiffany Miller’s home shortly before the victims’ bodies were discovered.

In September, 2024, the Mississippi Supreme Court issued a shocking 4-3 decision denying Willie the right to pursue his claim in the circuit court, despite the erosion of the evidence given at Willie’s trial. In a surreal twist, the majority judges speak of justice for Tiffany and Jon without acknowledging the possibility that their murderer is still at large.

Issues with this Case

Willie has many serious issues to raise, including:

- No physical evidence was found to link him directly to the murders. Footprints found at the murder scene did not match his footwear.[i] Fingerprints were found at the crime scene that did not belong to the victims or any other known person, but none of them belonged to him.[ii] None of the hair, blood or fibers found at the scene corresponded with his.[iii]

- None of the items supposedly missing from the victims – two watches, a class ring, and perhaps a necklace – was linked to him.[iv]

- No physical evidence linked Willie to the car burglary.[v]

- There was no proof that the car burglary was linked to the murders.[vi]

- John Wise, who was one of Steckler’s fraternity brothers, identified a token found at the murder scene as one that had been in his car; but the crime scene token was a shiny gold color, whereas Wise described his token as having lost its shine. There were no fingerprints on the token,[vii] and four Mississippi Supreme Court justices noted that the token may not have come from Wise’s car.[viii] The state alleged that Willie had a jacket that belonged to Wise; but Wise had difficulty identifying the jacket as his, and evidence suggests that the police believed Willie had bought the jacket (see more here). The prosecution claimed that a huggie reported missing from Wise’s car was found in the proximity of Willie’s home; but it was actually found 5 miles from his home (see more here). Fingerprint lifts from the burgled car were not analysed until 2015 (see more below).[ix]

- The State accepted that Willie had alibi evidence up to 11 pm on the evening of the murders (he was at the 2500 Club, on the other side of Starkville). During post-conviction investigations several witnesses stated that they saw Willie at the club later than 11 pm, including between midnight and almost 1 am.[x] See more here.

- FBI hair testimony given at Willie’s trial was flawed. The expert wrongly stated that hair fragments vacuumed from the floor of Miller’s car belonged to an African American;[xi] the prosecutor then amplified this error by linking this hair to aspects of the case which the jurors had been led to associate with Willie.[xii] In other words, “The FBI agent provided false testimony that was then used by the prosecutor at trial to suggest to the jury that Mr Manning was in the victim’s car.” (See more here.) [xiii]

- FBI expert ballistics testimony given at Willie’s trial has also been shown to have been flawed.[xiv]

Scientific developments since 2013 have confirmed the invalidity of the firearms testimony given at Willie’s trial. - The State failed to disclose exculpatory evidence about three of its witnesses, Earl Jordan,[xv] Frank Parker[xvi] and Paula Hathorn[xvii] (including evidence about the witnesses’ incentives to testify in favor of the State e.g. Hathorn received the enormous sum of $17,500, and had the penalties for pending criminal charges hugely reduced). Yet the prosecutor himself highlighted the crucial role of witnesses in the outcome of the case.[xviii]

And see additional information about incentivized witness testimony in affidavits contained in Willie’s motion filed in the Mississippi Supreme Court in September 2023. - Secretly recorded tapes and transcripts of a telephone conversation between Willie and Hathorn were not presented to the jurors. This conversation reveals Hathorn’s role as an undisclosed State agent (she asked questions provided by the Sheriff). Willie’s replies were not incriminatory; however, Hathorn herself contradicted her court evidence (e.g. saying that she did not know anything about someone shooting at a tree), and stated that she was being threatened with prosecution.[xix]

- In 2005, Hathorn signed an affidavit outlining the reward and concessions she received and the pressure she was under by law enforcement to get Willie to confess: “Several times Sheriff Bryan pressured me to try to get Willie to confess or talk about the case… Willie did not tell me he did anything at all to the students. He said he had nothing to do with that.” (See more here.) [xx]

- Another key witness, Earl Jordan (a jailhouse informant), made inconsistent statements and an improbable “confession” involving four people being in a two-seater car, when one of those four was actually incarcerated in Alabama at the time of the crime (see more here).[xxi]

- This witness (Jordan) was also able to pass a polygraph (lie detector) test implicating someone else in the crimes even before he supposedly heard Willie “confess” (see more here).[xxii]

- The State used Frank Parker as a witness despite a warning by his uncle that he was likely to be unreliable (see more here).[xxiii]

- The prosecutor improperly labeled Willie as a ‘monster’.[xxiv]

- African American people were improperly kept off Willie’s trial jury (4 Mississippi Supreme Court justices noted there was “a pattern of impermissible racial discrimination by the prosecution in jury selection”). See more here.[xxv]

- Willie’s trial attorneys were ineffective at the penalty stage.[xxvi]

- There is a possible pattern of reliance on testimony procured unfairly (see below for points from Willie’s 1993 [Jimmerson-Jordan] case).[xxvii]

[i]Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Page 9. Print.

[ii]Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 7 – 8. Print.

[iii]Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 7 – 8. Print.

[iv] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 9 – 10. Print.

[v] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 8 – 10. Print.

[vi] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Page 8. Print.

[vii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Page 9. Print.

[viii] Willie Jerome Manning A/K/A Fly v. State of Mississippi, 2013-DR-00491-SCT. Order. Supreme Court of Mississippi. April 25, 2013. Justice Kitchens’ Dissent. Page 8. Web, June 15, 2017.

[ix] Willie Jerome Manning versus State of Mississippi, 2013-DR-00491-SCT. Motion for Fingerprint Analysis. Circuit Court of Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, filed April 27, 2015. Pages 1 – 2. State of Mississippi Judiciary. Web, April 29, 2015.

[x] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis, filed in the Supreme Court of Mississippi. Filed March 22, 2013. Pages 24 – 26. Print.

[xi] U.S Department of Justice letter dated May 4, 2017, from John Crabb Jr, Special Counsel. To Forrest Allgood, District Attorney’s Office. Re Manning v. Mississippi, 2013-DR-00491-SCT.

[xii] Willie Jerome Manning versus State of Mississippi, Cause No. 2001-0144-CV, Supplemental Motion for Leave to Invoke Discovery and for Testing of Evidence. Circuit Court of Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, September 25, 2001. Pages 3 – 4. State of Mississippi Judiciary. Web. June 29, 2015.

[xiii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, 2013-DR-00491-SCT. Reply to State’s Opposition. Supreme Court of Mississippi. May 6, 2013. Page 4. Web, June 16, 2017.

[xiv] U.S Department of Justice letter dated May 6, 2013, from John Crabb Jr, Special Counsel. To Forrest Allgood, District Attorney’s Office. Oktibbeha County, MS. Re Manning v. Mississippi, 2013-DR-00491-SCT.

[xv] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis, Supreme Court of Mississippi. Filed March 22, 2013. Pages 10 – 11 and 12 – 13. Print.

[xvi] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 21 – 24. Print.

[xvii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 14 – 21. Print.

[xviii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 20 – 21. Print.

[xix] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 17 – 21. Print.

[xx] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi. 2001-0144-CV. Petition for Post-Conviction Relief. Filed in the Circuit Court for Oktibbeha County State of Mississippi. October 8, 2001. State of Mississippi Judiciary. Exhibit 29, pages 333 – 335.Web. June 29, 2015.

[xxi] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi. 2001-0144-CV. Petition for Post-Conviction Relief, filed in the Circuit Court for Oktibbeha County State of Mississippi. October 8, 2001. State of Mississippi Judiciary. Page 22 (page 30 of pdf).Web. June 29, 2015.

[xxii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi. 2001-0144-CV.Petition for Post-Conviction Relief, filed in the Circuit Court for Oktibbeha County State of Mississippi. October 8, 2001. State of Mississippi Judiciary. Page 19 (page 27 of pdf).Web. June 29, 2015.

[xxiii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 22 – 23. Print.

[xxiv] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi. 2001-0144-CV. Petition for Post-Conviction Relief, filed in the Circuit Court for Oktibbeha County State of Mississippi. October 8, 2001. State of Mississippi Judiciary. Page 80 (page 88 of pdf).Web. June 29, 2015.

[xxv] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 48 – 61. Print.

and Willie Jerome Manning A/K/A Fly v. State of Mississippi, 2013-DR-00491-SCT. Order. Supreme Court of Mississippi. April 25, 2013. Justice King’s Dissent. Page 18. Web, June 15, 2017.

[xxvi] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 64 – 79. Print.

[xxvii] Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi, Motion for Leave to File Successive Petition for Post-Conviction Relief including DNA Testing and other Forensic Analysis. Supreme Court of Mississippi, filed March 22, 2013. Pages 26 – 28. Print.

More about Forensics in this Case

It was the Steckler-Miller case that brought Willie close to execution on May 7 2013, following a 5:4 decision by the Mississippi Supreme Court that denied him his request—first made in 2001—for DNA testing of biological evidence from the murder scene and analysis of fingerprints found in the car belonging to one of the victims. The dissenting judges issued separate statements that included the following:

“Manning presented evidence at trial that undermined the State’s case against him.”

They also noted that DNA testing might enhance public safety by identifying unknown perpetrators.

Shortly before Willie’s scheduled execution, as part of their review of widespread flaws in FBI forensic evidence, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) sent three letters to officials in Mississippi admitting that FBI expert testimony given at Willie’s trial regarding hair and ballistics was flawed. Two of the letters were about hair testimony.

The first letter revealed the error made when the FBI hair analyst gave the jurors a general explanation of microscopic hair comparison: he wrongly ‘stated or implied’ that a hair could be ‘associated with a specific individual to the exclusion of all others’. The second letter focused on another error: in a written report the analyst stated unequivocally that some of the hair tested in Willie’s case (fragments vacuumed from the floor of Miller’s car) was ‘of Negroid origin’, and in testimony he described it as being ‘African American’. The letter tells us that this ‘exceeded the limits of science’: he should instead have testified that the hair exhibited traits associated with African Americans.

The FBI offered to provide testing of relevant hair evidence or related biological evidence.

The third DOJ letter outlined the errors that were made in ballistics analysis:

“The science regarding firearms examination does not permit examiner testimony that a specific gun fired a specific bullet to the exclusion of all other guns in the world.”

The Mississipi Supreme Court issued a Motion to Stay Execution to Willie only 4 hours before the scheduled execution time on May 7 2013. The decision was widely reported, including in The Huffington Post. The Court issued a further order on July 23 2013, unanimously reversing its earlier 5:4 decision to deny testing. No reason was given for the reversal, but presumably all judges now embraced views originally held only by the minority.

The July 23 2013 Court ruling also denied Willie his request for hearings to consider the reliability of expert testimony regarding ballistics and hair analysis. A further request, to have his convictions set aside, was also turned down.

Evidence that might be suitable for DNA testing was located in April 2014. It was dispatched to an Orchid Cellmark lab in Dallas, Texas, later that year. The results from preliminary testing were made public on June 8 2015:

Rape kit

Three swabs were tested for semen. One was found to be positive, and the other two were inconclusive. All three were approved for further testing (DNA extraction and quantification to determine whether any male DNA was present).

Pubic hair

The sample of pubic hair combings was inconclusive for semen, so was approved for DNA extraction and quantification to determine whether any male DNA was present. The sample of pubic hair was negative for semen; no further testing on this sample is planned.

Fingernail scrapings (from both hands of both victims)

Preliminary testing established the concentration of human and male DNA present. The samples were approved for a further process to increase the concentration of DNA, to determine whether any male DNA profile was present that did not originate from the victims.

Hair from victims’ hands

Orchid Cellmark found that no hairs were present in the evidence marked as “hair in Miller’s right hand” or the evidence marked as “hair in Steckler’s left hand”.

However, after Orchid Cellmark’s merger with Bode Technology late in 2015, these hairs were listed as available for testing.

Only one hair from Miller’s hand was available: it was processed and produced a partial mitochondrial DNA profile.

Five hairs from Steckler’s hand were processed. Of these, one produced a full mitochondrial DNA profile, three produced a partial mitochondrial DNA profile, and one did not produce a reportable mitochondrial DNA profile.

Fingerprints

In 2015, forensic specialist Ron Smith was asked to compare the fingerprints found at the murder scene and on John Wise’s car with fingerprints contained in FBI databases, to identify any potential matches. In 2016 Smith concluded this process by reporting that no potential matches had been found.

Request for specialist testing of hair fragments

In 2019 hair fragments from Tiffany Miller’s car were sent for testing by Bode Technology. Following this testing, Bode recommended sending some of the evidence to another lab, MitoTyping Technologies, which has a much higher success rate in finding mitochondrial DNA in very small, very old hairs.

Willie asked to transfer seven hair fragments from Miller’s car to MitoTyping Technologies; however, this request was denied by the circuit court in 2020 and the Mississippi Supreme Court in 2022. The circuit court decision included the puzzling statement that the hairs from Miller’s car were irrelevant to the outcome of Willie’s case – despite the hairs having been admitted as state evidence at his trial. (As Mississippi Supreme Court Justice King states in his 2022 dissent, “some of the hair samples were directly used to convict Manning”.)

Willie asked the US Supreme Court to review the decision to deny further DNA testing. His petition notes the unfairness of arbitrarily limiting the right to DNA testing:

“There was no way for Manning to know from the outset that the hair samples had problems and that the initial lab would be unable to develop profiles. Only after the first lab attempted and failed to develop a mtDNA profile would Manning have known to look for another lab. Essentially, if Manning had guessed right and selected the most appropriate lab when the Mississippi Supreme Court first authorized testing, he could very well have had suitable profiles developed. Instead, he guessed wrong.” See P.36 of petition (P. 42 of pdf).

The petition was denied.

Other Issues with this Case

A crucial deadline for this case was missed in 2000 because the state court appointed first one, then another unqualified lawyer to defend Willie.* These lawyers failed to file appropriate papers and did nothing but seek to withdraw, citing their own inexperience and inappropriate qualifications. Meanwhile, Willie found a qualified lawyer who sought to represent him, but the Circuit Court failed to act on this motion.

On July 17, 2012 the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit blamed Willie for the confusion leading to this missed deadline. It failed to recognize Willie’s efforts to procure the attorney of his choice; and the fact that incarceration meant that effective self-representation was impossible. The United States Supreme Court declined to review the case. See more here.

*Willie Jerome Manning v. Christopher Epps. 10-70008. Supplemental Brief of Petitioner-Appellant. In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi. Filed August 8, 2011. Pages 14 – 29 (19 – 34 of pdf). Print

Further Information about this Case

Andrew Cohen wrote extensively about this case in The Atlantic in May 2013: you can read his analysis here, here, here and here. You can also watch a video analyzing the case at Democracy Now.

Former policeman, Vincent Hill, believes that the students’ murders indicate not robbery, but a crime of passion:

(At 12.30) ‘I think if it was a robbery it would have happened right there, and there would have been no ride into the woods, and “I’m going to shoot the boyfriend in the back of the head, execution style, and then I’m going to run him over because I hate him so much, even though I’ve just met him 10 minutes ago, and then I’m going to shoot the girl in the face”…

(At 50.10) I do believe that was a crime of passion. Unfortunately, I’ve said it, and I’ll say it again – there’s someone out there that has gotten away with this murder, because just looking at the wounds, especially to Tiffany, they were personal. They were personal, they were personal, you know. That does not happen in a robbery. It just doesn’t happen.’

(See more here.)

Hill also finds it odd that no witnesses reported seeing blood on Willie’s clothes (see more here).

1993 JIMMERSON-JORDAN CASE (BROOKVILLE GARDEN CASE): EXONERATED

Events Leading to Willie’s Conviction

At approximately 8:30 p.m. on January 18, 1993, the bodies of Emmoline Jimmerson and her daughter, Alberta Jordan, were found by neighbors on the floor of their apartment in Building 10D of the Brookville Garden Apartments, Starkville, Mississippi. The women were last seen alive about 3 hours before this. Both were badly beaten with an iron found in a back bedroom of the apartment, and both had suffered slash wounds to the front of their necks.

Issues with this Case

In May 2013 Oktibbeha County Circuit Judge Lee Howard denied Willie a post-hearing memorandum in this case. Appealing this decision, Willie stated in two briefs, submitted December 2013 and May 2014, that this case involved substantial allegations of State misconduct resulting in wrongful conviction. He made the following points:

- The crucial State witness, Kevin Lucious, committed perjury at Willie’s trial when he testified he watched from his apartment in Brookville Garden as Willie entered the elderly ladies’ apartment opposite. (Lucious’s trial testimony was unequivocal that he watched from his apartment; yet police canvass notes show that this apartment was vacant at the time, and that Lucious was not then living in a Brookville Garden apartment*).

- The State erred in failing to disclose these police canvass notes to Willie’s trial counsel.

- The State was mistaken in asserting that other witnesses corroborated Lucious’s trial testimony about seeing Willie enter the apartment: no other witness confirmed this.

- Lucious testified at a post-conviction hearing that none of his trial testimony was true, and that he had lied because of pressure brought by the State.

- Another witness, Herbert Ashford, undermined his own credibility by making statements that were contradictory.

- The State erred in failing to disclose a crime lab report showing that a bloody shoe print next to one of the bodies could not have been left by Willie (the shoe print was size 8, whereas Willie’s shoe size is 10½ – 11).

- Willie’s trial counsel was deficient in: failing to impeach Lucious; failing to interview Willie’s brother, Marshon Manning, and call him as a witness; failing to investigate Ashford or interview Teresa Bush, who was then living with Ashford; failing to investigate other possible suspects; and failing to investigate the shoeprint.

- At the evidentiary hearing the Oktibbeha County Circuit Court erred in refusing to authorize for presentation all the documents that Willie had requested.

- Forensic evidence yielded no clues as to the perpetrator. There were no prints found on the weapons used against the victims, and law enforcement found no DNA, fibers, prints, or other physical evidence that pointed to any suspect.

- Law enforcement made no arrest for well over a year following the homicides.

- Amicus briefs submitted on Willie’s behalf point out that perjured testimony is the most common cause of wrongful conviction, especially in capital cases; and that incentivized witnesses contribute to these false convictions. See more here.

*Record Excerpts from this case, including the Police Department notes and the Mississippi Crime Laboratory footwear case notes, are available in Willie Jerome Manning v. State of Mississippi. 2013-CA-00882-SCT. Appellant’s Corrected Record Excerpts. Dec 13, 2013. Page 36 of pdf. Web, June 19, 2017. The police canvass notes (page 36 of the document) show that Kevin Lucious was not living in Brookville Garden at the time of the murders. (The murders occurred on January 18, 1993; Lucious moved into Apartment 11-E on February 1, 1993; Apartment 11-E was vacant when the murders happened. The police canvass notes were not disclosed by prosecutors to Willie’s trial counsel.)

The oral argument for this case was heard in October 2014; a video showing this can be viewed here, and you can read about it here. The court heard arguments from the defense and the State, focusing on the recanted testimony and the two pieces of evidence that were not available to the trial defense attorneys (police canvass notes and evidence about the size of the shoe print). During the oral argument Justice Dickinson raised the possibility of improper conduct by the State:

“…the two pieces of information that are missing are pieces of information that it seems at least arguable would have been favorable to Mr Manning’s defense. And they’re both missing from the files that were provided to defense counsel. Do you find that odd?” (see October 2014 oral argument video, 1:25.30).In a 7:2 decision on February 12 2015, the Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the judgment of the Oktibbeha County Circuit Court which had denied Willie post-conviction relief. The Mississippi Supreme Court also reversed Willie’s conviction and sentence and remanded the case to the trial court for a new trial, declaring:

“the State violated Manning’s due-process rights by failing to provide favorable, material evidence.”You can read a report about the Mississippi Supreme Court’s decision in this case in the Clarion-Ledger.

On April 20 2015 Judge Lee Howard (Oktibbeha County Circuit Court) signed an Order of Nolle Prosequi, stating that “…Due to the fact that a material witness for the state has now changed his testimony in this case on a number of material issues, the State is unable to meet its burden of proof”. In other words, the prosecutor, Forrest Allgood, did not wish to prosecute this case in a new trial; this closes the case. As a result, the Death Penalty Information Center has listed Willie as the 153rd death row exoneree.

The order lists points made by Kevin Lucious in an affidavit that he gave on January 10, 2002, viz.

- His motivation for committing perjury was fear of being charged with the two murders.

- Sheriff Bryan and Captain Lindley prepared a false statement for him.

- He signed the statement only because District Attorney Forrest Allgood had told him he would not be charged with capital murder if he cooperated.

- He did not see Willie enter the victims’ apartment near the time of the murders.

- He never told Sheriff Bryan that he had seen Willie going into the apartment.

- He told Sheriff Bryan that Tyrone Smith had confessed to the murders and that Smith had disposed of the murder weapon near the crime scene.

- Willie never told him “he would not have killed the old ladies if he had known the [sic] didn’t have money”.

- Willie never told him “he went into the ladies’ apartment or did anything to them”.

You can read a report about the prosecutor dropping charges at Jackson Free Press. You can watch a video from an Al Jazeera America program showing Lucious’s former girlfriend describe the pressure to testify against Willie (second video clip on the page); a transcript of this interview is available here.

Other Information about Willie’s Cases

- Former policeman, Vincent Hill, is puzzled (at 40:00) that Willie was convicted in a second case when the method of murders was very different from that in his first case:

“It doesn’t make sense… People are creatures of habit. Even serial killers are creatures of habit. They kill the exact same way every time… You don’t go shooting someone and then the next day saying, ‘No, that was too noisy – I want to stab them’.” (See more here.) - Willie was vilified by the prosecutor in 2006, following the reversal of a Mississippi Supreme Court decision which had previously overturned both of Willie’s convictions (see more here).

- Willie had no history of violence and was known as a peaceable person (see more here).